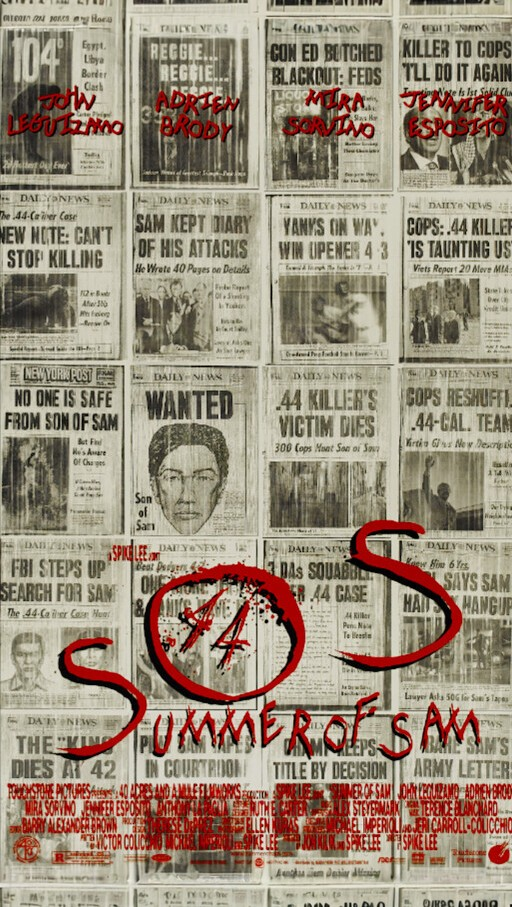

Explore how Summer of Sam captures the psychological impact of fear and mass hysteria during NYC’s terrifying 1977 serial killings.

Welcome to the boiling, bloody psyche of a city on the edge. This is not just a movie review. This is psychological autopsy. This is Summer of Sam.

THE PSYCHOLOGY OF FEAR: THE SUMMER THAT SHATTERED NEW YORK

What happens when a city becomes a pressure cooker?

When every man, woman, and child walks outside thinking they might be next? That’s not suspense. That’s psychological warfare.

Fear, in its clinical definition, is the emotional response to a perceived threat. But in the Summer of Sam, it mutates into a virus—airborne, psychological, and contagious. Fear dominates not just the streets but the very bloodstream of New York City.

According to the American Psychological Association, prolonged exposure to fear can trigger hypervigilance, chronic anxiety, and paranoia. Sound familiar?

In the summer of 1977, David Berkowitz, dubbed “Son of Sam,” plunged NYC into a waking nightmare. But the real killer? It wasn’t just a man with a .44 caliber pistol—it was the psychological carnage that followed. The lights were out. The city was hot. The people were desperate. Every parked car became a death trap. Every neighbor a suspect.

Think about it: How does a metropolis begin to suspect its own shadow? That’s fear morphing into collective psychosis—a term psychologists use when an entire group starts sharing delusional thinking. By July, New Yorkers weren’t just afraid—they were breaking down. Even the NYPD admitted to receiving over 75,000 calls per day during the peak of the attacks. Fear wasn’t a response anymore. It was identity.

This movie doesn’t just show fear—it injects it into you like a dirty syringe in an alleyway. You feel the panic, the sweat, the sleepless nights. It’s raw, suffocating, and clinically accurate in its portrayal of mass psychological unraveling.

(SUMMER OF SAM) – THE SERIAL KILLER ARCHETYPE: UNDERSTANDING DAVID BERKOWITZ

Let’s dissect the monster behind the mayhem: David Berkowitz. A mailman by day, a delusional killer by night. But what does psychology say about him?

Serial killers often fall into clinical patterns. Berkowitz was no exception—textbook signs of Antisocial Personality Disorder (APD): lack of remorse, disregard for others, impulsivity. But peel deeper, and Narcissistic Personality Disorder (NPD) starts to scream from beneath the surface. He wrote taunting letters to the press. He craved attention. He needed to be feared.

FBI profiler John Douglas once said, “Serial killers are like sharks. They need to keep moving, keep feeding—or they die.” Berkowitz wasn’t just hunting victims; he was feeding an ego bruised by childhood trauma, rejection, and a sense of invisibility.

Berkowitz claimed a demon-possessed dog told him to kill. Sounds like schizophrenia, right? Not quite. Forensic psychologists argue that Berkowitz showed signs of schizoaffective disorder—a hybrid of psychosis and mood instability. But others say it was all an act. A calculated smokescreen. Either way, he painted his madness in blood across the city walls.

The Summer of Sam doesn’t dwell on Berkowitz. Smart move. It treats him like a shadow, which makes him more terrifying. Because that’s what real psychopathy does—it hides in plain sight.

MOB MENTALITY AND COLLECTIVE PSYCHOSIS IN NEIGHBORHOODS

Forget Berkowitz. The real savagery came from the people who weren’t pulling the trigger.

Mob mentality—first defined by Gustave Le Bon in The Crowd (1895)—is when individuals in a group lose their personal identity and moral compass. In Summer of Sam, this plays out in brutal, tribal fashion. Friends turn on friends. Neighbors become informants. Suspicion devours logic. Sound familiar?

As the city melts under the pressure, the Bronx becomes a psychological battlefield. Ritchie—punk, sexual deviant, perceived “other”—becomes the scapegoat. Because when the real killer is invisible, the mob finds someone visible to blame.

Psychologists call this displacement: redirecting fear and anger toward an innocent proxy. And in 1977, that proxy wore leather, eyeliner, and listened to The Who.

A 2020 study in the Journal of Social Psychology found that people under stress are 60% more likely to conform to mob behavior, especially when fear is involved. That statistic alone explains half of this film’s chaos.

When the mind loses safety, it seeks control—even if that control is built on a lie. That’s what happens in Summer of Sam. And it’s brutal. It’s real. It’s human nature at its worst.

Leave a Reply